You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Allyn Ann McLerie’ tag.

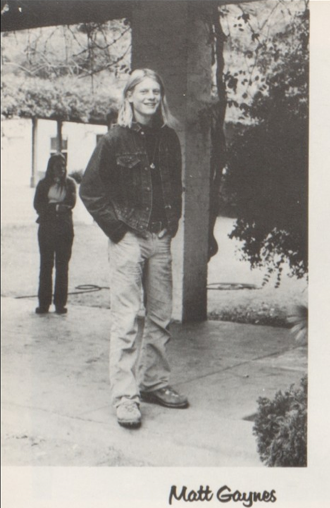

If Matt Gaynes were alive today, he would be a mature man in his mid-fifties. The height might have diminished by a couple of millimeters, or perhaps that inexorability would not have yet begun; either way, he would still routinely be the tallest one in the elevator. His blonde hair would have lost the almost metallic golden sheen the sun glinted off of in Nantucket in 1973; time would have softened it to the tan beach sand of his father, George. He would dress with a casual unfussy formality, blue blazers and chinos, because it would be an easy uniform to slip into and respectful of the people he encountered, whoever they might have been.

If Matt Gaynes were alive today, he might have the tiniest bit of a belly, from beer and wine and casually enjoying life, but he would be disciplined enough to keep it from defining him, and if he ever felt it was he would get to the gym or cut out the carbs and make it go away. The boy may have, at times, run a bit wild, but the man would have held his appetites in check.

If Matt Gaynes were alive today, he would no doubt be a father, and a damn good one. His professional desires would have settled, perhaps into something surprising, most likely to do with sports or athleticism. Teaching might have been some part of it. As a boy, and as a man, he expressed leadership effortlessly, in every arena he encountered. He had a gift of taking whatever crazy idea interested him and making it possible.

That’s important to understand. Ed Ruscha has a deceptively simple 1977 painting entitled No End of the Things Made of Human Talk. I have no idea if Matt ever saw it, but I’m absolutely sure it would have at once been instantly recognizable to him, and its simple directness would have caused him to burst out with a crisp, short bark of a laugh. Because talk was never the end for him. Talk achieved nothing if it didn’t turn into action. The boy, and then the man, turned suggestions into achievements seemingly effortlessly, even when they were ridiculously hard.

Especially when they were ridiculously hard.

He was in school on Catalina Island, sent there as a teenager by his parents George and Allyn Ann because (as has been chronicled elsewhere in this blog) the drug culture had made its inroads into him and he into it. The school turned out to be perfect for him, a place that allowed him to shed old identities and necessities and mature into new and more meaningful ones. (I wasn’t there; I was in New York fighting my own battles, though I did visit the island with him years later.) One night, one of Matt’s Catalina Island School classmates suggested they get beer. This was for whatever reason, an impossibility on the island. But at the school they had access to kayaks—there were classes in building them—and it was only 22 miles across open ocean to Long Beach. So Matt led a couple of kayaks across one of the world’s most heavily trafficked ocean corridors at night. For beer. And got it, stowed cases in the kayak holds, and then turned around and paddled 22 miles back.

Easy. Not for me, nor for anyone else. But for him, yeah.

Water always played a part. He and I learned to swim at the YMCA on 8th avenue; it’s an apartment building now. The pool was municipal-sized, laned and busy, and we went once a week, and dove in full-throated little-kid competition for a heavy rubberized brick thrown from the side over and over again. This was when I first came to know the absolute joy of being entirely surrounded by water; to this day I have no interest in swimming laps unless I’m holding my breath and trying to get all the way across the pool without ever touching air.

And then I love it.

Matt’s relationship with water was richer than mine. Once he discovered kayaking he never stopped, and lived in Santa Barbara in easy proximity to the beach, if by easy proximity you mean going a hundred stairs down a steep cliff with a kayak over your shoulder. He introduced the term “hairball” into my vocabulary (it describes particularly dangerous whirlpools), and was good enough, and a known quantity enough, to just barely miss qualifying for the 1980 Olympics, the year Carter cancelled American participation after the Russians invaded Afghanistan. And then he broke his wrist—I have the x-rays in a box in my closet—and lost whatever fraction of a millisecond of control is needed to join the Olympians. But he wasn’t stuck on that; he was too broadminded a participant in life to get trapped by that self-definition.

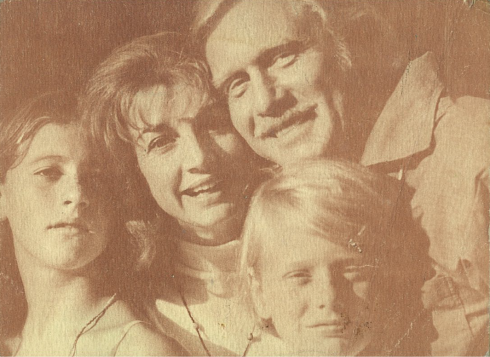

He and I were born the same year, August for me and November for him, spent our first nine years in the same New York apartment building, four floors from each other—6A and 10C. His number was CI6-5855, when CI stood for Circle. Mine was JU2-8940, for Judson. I am an only child of only children; Matt had an older sister, Iya, who was from birth and very much remains a force of nature in her own right, (She was for many years involved in high-level city politics in Santa Barbara, and recently embarked on a new marriage; her daughter, Matt’s niece, has built a beautiful family on the West Coast.) We had a male pug, Thing; they had a female keeshond, Saskia. Matt’s mother and father were actors; my mother was an actress and my father a writer. He was blonde and thin and outgoing. I was brown-haired and perpetually chubby and introverted—at least I was then; at some point I inarguably became an extrovert, to the extent those overused labels still apply, though unfortunately the chubby thing never left.

Matt’s father, George Gaynes, had done movies, Broadway and off-Broadway; he was The Tongue in Tootsie who serenaded Dustin Hoffman’s character from the street. He did turns on Punkie Brewster and the Police Academy comedies, and was absolutely brilliant as Serybryakov in Louis Malle’s Vanya on 42nd Street. His mother, Allyn Ann Mclerie, was a triple threat—actress-singer-dancer—who was in the original production of On the Town on Broadway, among other era-defining musicals, and had steady work in theater, TV and movies for years; people know her from Days and Nights of Molly Dodd, though she’s in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? and All the President’s Men and Jeremiah Johnson along with many others. She worked a lot with Robert Redford. George and Allyn Ann were both in The Actor’s Studio, back in the ‘50s and ‘60s when all the cool people were there. Which basically means they knew everybody.

Matt didn’t care about any of that. Or rather: he admired it, and respected it, and was active in his appreciation of the fine things all that work had allowed for him, but he didn’t feel the call to do those things. It was what his parents had done; it was not an inevitability for him, not an entitlement he felt he owned. From George he’d gotten his height, his Dutch golden hair and straight back and courtly European manners; from Allyn Ann he’d gotten her Scottish passion and focus and capacity for quick anger at perceived injustice. The only movie I know him to be in is the opening-credits song in the Val Kilmer comedy Top Secret, a very funny Beach Boys surfing-USA spoof in which happy American teenagers surf and skeet-shoot at the same time. He’s one of the gun-toting surfers; it could well be him who appears to get off a shot before being crushed by a wave more than twice his size behind the Director of Photography credit. Maybe he had talent as an actor; certainly it was in his genes. All that can be said from this, which I believe is his only appearance in film, is that as an actor his surfing skills are impeccable.

Let’s get this out of the way now: Matt died in a car crash in India in 1989. Recently married (I was the best man at his wedding, earlier that year) he was traveling through Northern India to Nepal to film a kayaking special for ESPN. The moment that he died was weirdly pivotal: worlds were changing. Almost immediately after his death the Berlin Wall came down. He would have relished it, not being a man with much use for walls or the dictatorships behind them, whether left or right.

But as I learned when my mother died, the body at its final age is not the sum total of the person’s existence. The body is a husk, too wounded by age or illness or trauma to continue its usefulness. Being overly concerned about Matt’s death is uninteresting. He was here; he walked the rocks of Catalina and the hills of Central Park, air bent around him and water curled around the edges of his paddle. He made a mark.

And yes, he’s somewhere else. And so is my mother, and so are they all.

On the other side of time, I expect, but I don’t know. I don’t know.

Who was he? That’s for people who knew him to explain. In the coming months and years those explanations will be part of the thread of this blog.

And now you know the reason I named it Nantucket ’73.

For drug-addled stories of Matt and me acting fairly disgracefully as teenagers, go here:

https://msbhall.wordpress.com/2012/07/08/the-nantucket-birthday-story/